The happiest of new year wishes to you and yours. In your house, New Year’s Day may be the time to nurse a hangover, watch a football game, or stay true, at least for one day, to that ambitious word count goal. My focus today is directed at none of these. I’d like to use the Trial-of-the-Month to focus on the 60th anniversary of a case that changed the legal landscape across the United States, Gideon v. Wainwright.

On the night of June 3rd, 1961, the Bay Harbor Pool Room in Panama City, Florida, had the front door forced. An unknown person entered the closed establishment and smashed a cigarette machine and a record player. The assailant stole money from the cash register.

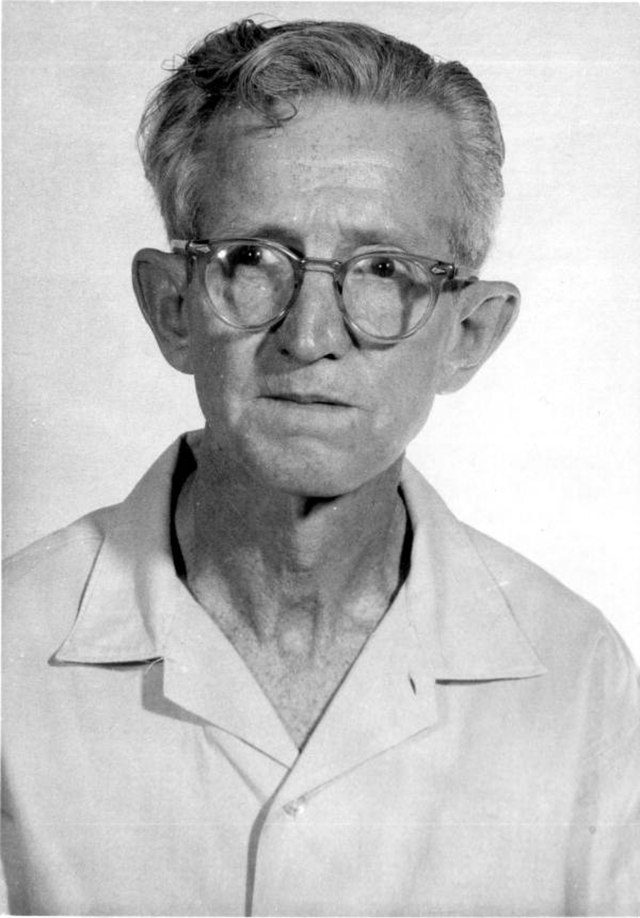

The police began investigating the burglary. An eyewitness, Henry Cook, reported that he had seen Clarence Earl Gideon at 5:30 am on the morning of the burglary, leaving the pool hall with change in his pocket and a wine bottle and a Coca-Cola in his hands. The police arrested Gideon and charged him with breaking and entering with the intent to commit petty larceny. The burglary was a felony under Florida law.

Appearing before the judge without funds or an attorney, Gideon asked the court to appoint counsel for him. The judge ruled:

“Mr. Gideon, I am sorry, but I cannot appoint Counsel to represent you in this case. Under the laws of the State of Florida, the only time the Court can appoint Counsel to represent a Defendant is when that person is charged with a capital offense. I am sorry, but I will have to deny your request to appoint Counsel to defend you in this case.”

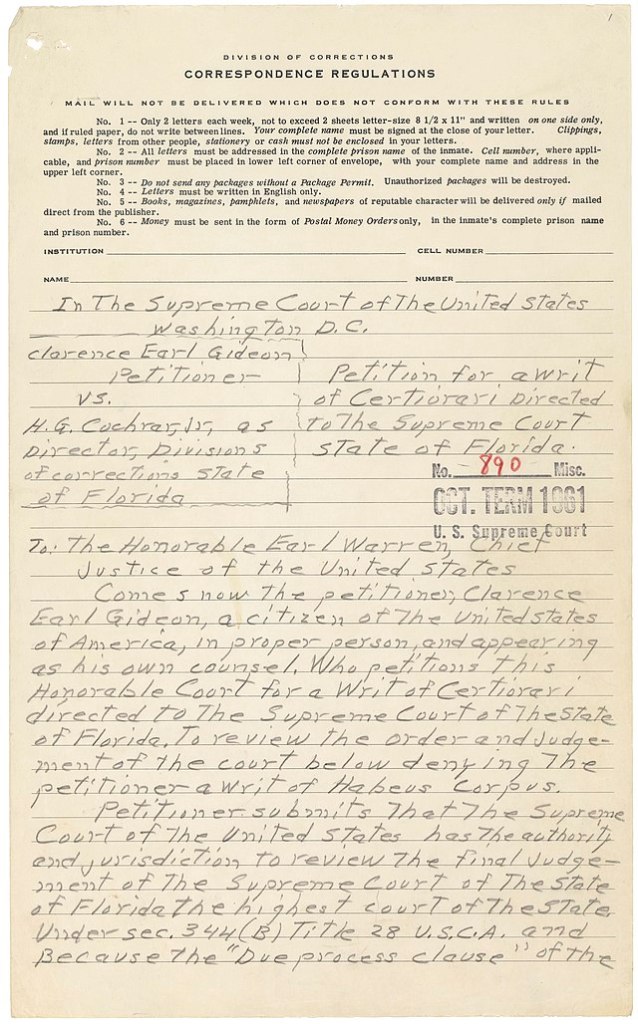

Clarence Gideon had an eighth-grade education. He ran away from home while he was in middle school. He drifted through life, spending time in and out of jail. Put to trial, he did the best he could by himself. He made an opening statement, cross-examined the government’s witnesses, presented witnesses on his own behalf, declined to testify in his own defense, and made a short final argument. The jury convicted Gideon, and he was sentenced to five years in the state penitentiary. He petitioned the Florida Supreme Court, claiming that his Sixth Amendment rights had been violated. The court denied his habeas corpus plea. From his cell at Raiford State Prison, Clarence Gideon appealed to the United States Supreme Court. The petition was handwritten in pencil on prison stationery. He again argued that he had been denied his Sixth Amendment rights and that those rights applied to Florida under the Fourteenth Amendment.

From the slush pile of letters and petitions the United States Supreme Court received, they accepted Clarence Gideon’s. The court appointed future Supreme Court justice Abe Fortas to argue the case on his behalf. The case was heard on January 15th, 1963. Among other points, Fortas argued the wide acceptance within the legal community that the first thing a lawyer does when accused of wrongdoing is to hire an attorney. If licensed members of the bar need an attorney to represent them in legal proceedings, how much more, he argued, does a man without a legal education or any education?

Eight weeks after the January arguments, the Supreme Court returned its decision. On March 18th, 1963, the court unanimously ruled that an indigent defendant’s right to the assistance of counsel is essential to a fair trial. They overturned Gideon’s conviction as a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

With an attorney beside him, Gideon was retried in August 1963. His lawyer undermined the testimony of Henry Cook, suggesting that he had been the lookout for the true burglars. He also delivered the testimony of the cab driver who had driven Gideon from the area that morning. His testimony established that Gideon carried neither a wine bottle nor a Coca-Cola. The second jury acquitted Clarence Earl Gideon.

In the Supreme Court decision, Justice Hugo Black wrote, “reason and reflection, require us to recognize that, in our adversary system of criminal justice, any person haled into court, who is too poor to hire a lawyer, cannot be assured a fair trial unless counsel is provided for him. This seems to us to be an obvious truth.” Sixty years later, we take the right to counsel as automatic. Inside the courthouse, we tend to look a little strangely at the defendants who do not take advantage of the right to counsel.

It is important to note that the Gideon decision only extended to felony offenses. In 1979, the Supreme Court ruled that a defendant was entitled to counsel whenever incarceration was an authorized penalty. Scott v. Illinois extended the right to misdemeanors above the level of citations.

The case changed the legal and literary landscape. It led to the creation of public defender’s offices. The overburdened public defender has become a literary and cinema trope. Henry Fonda played Clarence Gideon in the movie Gideon’s Trumpet. From the standpoint of public policy, every taxpayer should be aware of the impact of the Gideon decision on criminal court budgets. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas is. He criticized Gideon in a 2018 decision, Garza v. Idaho, noting in part the budgetary impact of providing defense counsel. Line-item budget analysis, however, may not account for the full social impact. Humanity may suffer if defendants lack representation when accused of a crime. One Clarence might explain those costs to the other.

Mark Thielman